I will never forget the week when the news broke about the Ampatuan massacre in 2009. I was an elementary student on the way to Ilagan, Isabela for a contest for campus journalists.

When we reached the city center, a number of foreigners were waiting for bus rides. They're probably just leaving the city, which was not unusual. But our adviser pointed out that they're probably leaving the country too, fearing the state of the country at the time.

At 10 years old, I was already afraid to continue my dream of pursuing journalism. This case taught me the price of truth at an early age. We were told that jounalism is a dangerous profession because it entails sacrifices, even if it means risking your life. As heroic as it sounds, I think it shouldn't be that way.

In every lecture I attended for campus journalism under the great Professor Ben Domingo Jr, he would always mention the two worst events for press freedom in the country: Marcos' Martial Law and the Ampatuan massacre.

After declaring Martial Law, Ferdinand Marcos' instruction was to take control over all newspapers, radio, and television networks. He silenced public criticism and controlled information. There were also detentions and disappearances of journalists. What followed were their deaths.

And the Ampatuan massacre – regarded as perhaps the worst political massacre and election-related violence in the history of the Philippines, killing 58 people, including 32 journalists – is also considered the single deadliest attack against the media in the world. Both events attacking journalists, destroying democracy and rooted in impunity. Years passed and no justice.

Now that Judge Jocelyn Solis Reyes had served the verdict of the Ampatuan massacre case on December 19, ending the almost 10-year trial that spanned 3 administrations, we must reflect on the lessons of the case and notice the patterns showed in the past few years:

1) Our slow and poor justice system has a lot to improve on, and the decision of the Quezon City Regional Trial Court is not yet final until the Supreme Court rules it so, but the verdict gives us and the families of the victims hope for justice.

2) There is an Ampatuan who remains free, acquitted, and in power, and he can get reelected despite numerous cases of corruption. (READ: [ANALYSIS] What the Ampatuan Massacre did not – and could not – address)

3) The mass murders were perpetrated by the police with orders from politicians, and both enablers should not be exempted from the law.

4) This case does not justify all cases of press violations.

The Philippine media is at risk again more than ever, given continuous disinformation, harassment, and threats of blocking franchise renewals and revocation of registration by the current administration. (READ: [OPINION] Even after the Ampatuan verdict, Filipino journalists are still in peril)

I had been writing about the Ampatuan massacre up to my days in college. But here, I write again as if I were 10 years old. What I knew at that time was I wanted to be safe if I became a journalist.

The Philippines remains to be among the deadliest countries for journalists in Southeast Asia. This should not be the future that awaits young journalists. We were not merely taught how to write, but to stand up for what we write. And it is our right to be safe in expressing our opinions and criticisms.

The fight of professional journalism will always be the fight of campus journalism. We celebrate the Ampatuan massacre verdict, hope for justice, and continue to address the struggles of press freedom.

For now, democracy and press freedom won. But we do not fight to win, we fight to be free. There is more to be done. – Rappler.com

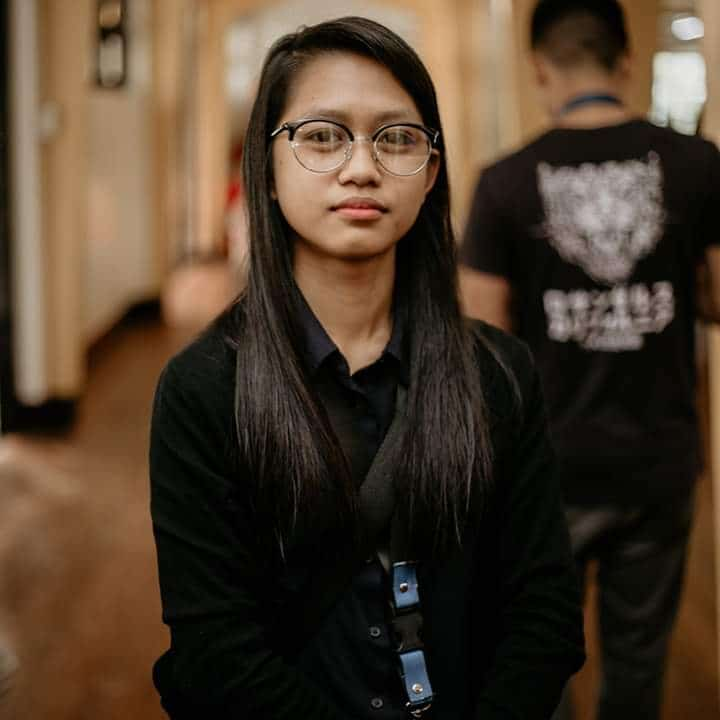

Diwa Donato is a Rappler mover and political science graduate from Saint Louis University, Baguio City. She dedicated 13 years to campus journalism from elementary to college. She is an advocate for youth empowerment, press freedom, and democracy. More at @diwadonato on Twitter.