MANILA, Philippines – Manila is crumbling.

I often hear this from disappointed tourists and politicians.

This year, I promised to explore the great capital more – to see if I would step on crumbs, as most people claim, or if my experience proves otherwise.

As a child, Manila was a faraway exotic land. My family barely left our small sleepy town, hence I could not relate to classmates bragging about vacationing in Manila to see famous paintings, to watch musicals, or to simply shop and dine.

We had none of those. I was envious. I only got to travel to Manila through episodes of Lito Atienza’s drama series Maynila. I knew the show’s opening song by heart.

As a teenager, I watched old copies of Lino Brocka’s Maynila sa Kuko ng Liwanag and Ishmael Bernal’s Manila By Night. Their version of Manila is completely different from Atienza’s.

In my mind, Manila morphed into a place of crime, sex, garbage, arts, and culture.

Until today, Manila maintains its mystique. Despite having studied and worked in Quezon City and Makati for years now, I have never truly known Manila.

Hassle

Going to Manila has always felt like a chore.

Before the boom of Grab and Angkas, one had to take several jeepney rides to reach Escolta, the Cultural Center of the Philippines, the National Museum, Intramuros, and all other famous Manila landmarks. My mother always worried I would get mugged during these trips.

Manila was also extra confusing before the rise of Waze and Google Maps.

The destinations were lovely, but a commuter’s journey isn’t.

Ride-sharing apps made going to Manila easier, but only for those who can afford it. These beautiful parks and museums – albeit having no entrance fees – remain inaccessible to many Filipinos.

Newly elected Manila mayor Isko Moreno has been generating media buzz for promising to restore the capital’s beauty and glory. Many are impressed by the mayor’s zeal.

Today, I met a few others doing their best to preserve our country’s heritage sites. They work silently, receiving little-to-no recognition, but their bare hands are literally reshaping today’s Manila.

Women get it done

To celebrate my birthday, I went to an exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Manila (MET). Incidentally, there were people at the lobby preparing for a “Heritage Walk” organized by the MET.

I wanted to join, but slots were limited and you had to pre-register. Luckily, two participants bailed and I got their slot.

Our group was a mix of young and old. I did not even know our destination. The next thing I knew, I was on a jeep heading to Paco Park.

It was my first time at Paco Park. I was clueless.

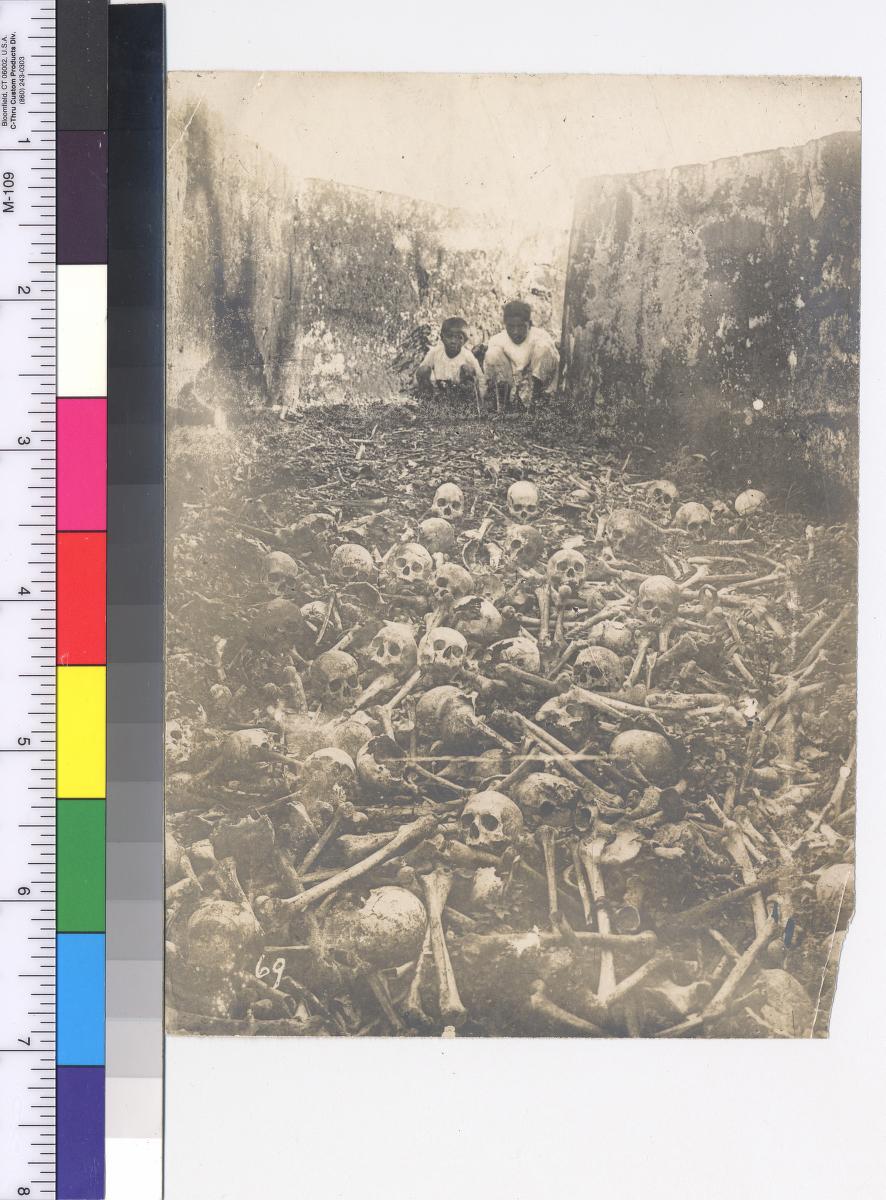

Completed in 1820, it was intended as a cemetery for Manila’s elites but was also used for victims of a widespread cholera epidemic during those times.

The Gomburza priests and Jose Rizal were once buried here. Rizal’s grave was “simple and nearly anonymous,” with his initials reversed to keep it unnoticed.

In 1912, burials were discontinued; remains were transferred elsewhere. In 1966, it was turned into a national park; the St. Pancratius Chapel inside the park has been popular for weddings. Finally in 2015, Paco Park was declared a "national cultural treasure."

After all it has been through, Paco Park stands still – not through some divine miracle, but through a carefully planned rehabilitation process.

Among those keeping Paco Park alive is a group of women.

At the heritage walk, I met Analisa, a 28-year old mason who was part of the conservation team that rehabilitated Paco Park's ossuary, in partnership with the National Parks Development Committee.

After two years, Analisa's team started wrapping up their opus in July 2019.

Out of the team's 8 members, 6 are women. They are trained in masonry, carpentry, plumbing, and electrical, wood, and metal work.

"Some say these jobs are not for women," Analisa told me in Filipino. "That's not true. Women can do whatever men can. We're not weak."

Analisa was a computer science student, but she had to drop out during her second year in college due to financial constraints. At 21, Analisa started her technical-vocational education and training (TVET). "I enjoyed it. I like getting things done," she said.

In the Philippines, TVET is yet to be fully understood and appreciated. Some might even frown upon TVET, misjudging it to be less valuable than a college degree. In the past two decades, however, the number of TVET graduates has increased, according to the Technical Education and Skills Development Authority (TESDA).

The K-12 program’s technical-vocational-livelihood strand is among the government’s latest efforts to remove stigma against TVET. In 2018, TESDA reported having over 2 million TVET graduates.

Analisa earned her training through Escuela Taller Filipinas Foundation, a non-profit organization focused on preserving heritage sites.

They train indigent youth on technical-vocational skills needed in heritage conservation. Their students have also contributed to preserving the Fort Santiago, Ivatan houses in Batanes, and other heritage sites like the San Agustin Church.

Analisa advises young Filipinos – especially women – to pursue TVET. “You can do it if you have patience and perseverance. Believe in yourself,” the young mason said.

“Technical and vocational skills are important, especially in protecting our heritage,” she added. “When I was growing up, I didn’t understand the value of cultural heritage. I hope today’s youth isn’t the same.”

Analisa’s favorite project so far is her team’s rehabilitation of the Malate Church, “because it was very difficult, but we were happy to see people appreciating our work after.”

Rise of mall rats

In our colonial past, heritage sites were destroyed by wars.

Today, our spaces are mostly threatened by mushrooms of malls and condominiums. And even by our mere lack of interest in our own history and culture.

“We cannot freeze development and our social fabric,” explained Jeffrey “Foom” Cobilla, our heritage walk tour guide and an architect from Escuela Taller. “However, whenever we want to alter our space – especially our heritage structures – we should think about it carefully,”

Heritage sites are protected under RA 10066 or the National Cultural Heritage Act of 2009. Unfortunately, like most of our laws, this one needs sharper teeth.

“What we want to do is to make communities more capable of caring,” said Foom. “More people should be involved either by participating in conservation projects or by simply raising awareness on the significance of our heritage.”

Just as I was leaving the gates of the famous cemetery-turned-park, I was already thinking of where to visit next week. I then noticed some residents voluntarily sweeping and collecting trash along the sidewalks of the street beyond Paco Park’s walls.

I realized Manila isn’t crumbling just yet – thanks to the likes of Analisa, Foom, and many others quietly keeping this great city afloat. – Rappler.com

Fritzie Rodriguez is a humanitarian and development worker.