Labels and templates are constraining – even in the context of gay rights.

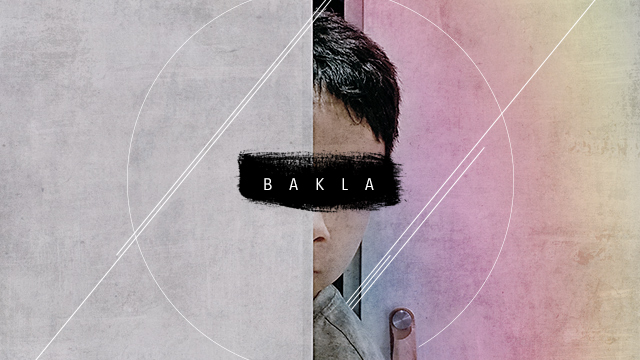

In the Philippines, if you are to look around and spot people who fall under non-normative sexual orientation, gender identity, and expression (SOGIE), you will more likely be faced with the image of flamboyant, screaming, and seemingly care-free males who often dress like females. This is the image of the bakla.

The bakla conflates SOGIE even though these 3 are independent of each other. Gender identity is one’s inner sense of self as a man, a woman, or neither; gender expression is the set of external characteristics that a person exhibits; and sexual orientation refers to one’s emotional, romantic, and sexual attraction to members of the same or the opposite sex. In many LGBT discourses, as in this article, the bakla is defined more in terms of gender identity than sexual orientation.

The identity of the bakla, moreover, oftentimes represents the plethora of identities constituting the community of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, asexual, and other sexualities (LGBTQIA+). Conversations on the rights of the LGBTQIA+ members typically include one phenomenon: coming out of the closet, loosely translated to the vernacular as paglaladlad.

The concept of coming out of the closet is no stranger to Filipinos. This is especially evident in the middle class, where coming out serves as a template for recounting personal stories. It is mainstream knowledge that telling others about your sexual orientation is a difficult yet liberating experience that enables people to come to terms with their identity. However, the lived experiences of some LGBTQIA+ members show that this is not always the case.

In April 2019, I was in a rural area in the Northern Philippines doing research on the experiences of poor teenage bakla. A common experience exemplified by their responses is that people have already called them bakla based on the effeminate way that my interviewees acted when they were young – too young, perhaps, for them to even understand the full gravity of the label that was thrown at them.

It is commonly assumed that acceptance of someone’s deviant SOGIE is a liberating experience. However, growing up with the tag of bakla weighs heavily on the shoulders of many, due to the expectations of who the bakla should be. These are highlighted by the fact that some of my interviewees do not conform with the mainstream conception that the bakla is attracted to another genitally male individual. In fact, some of them are bisexuals and few of them still have not figured out their sexual orientation.

Nonetheless, they are afraid of telling both their relatives and friends about their sexual orientation because they fear stigmatization and resentment from people who are close to them. This is arguably their version of the dreaded process of coming out – saying that they are not attracted, at least only, to another male. They are afraid to say it because by doing so, they will change from an identity that is perceptively tolerated by their community to an identity that may arouse further criticism and resentment.

There is a societal expectation that the bakla should be attracted only to biological males, so the baklas who are attracted to other sexual identities become even more socially deviant. In this respect, therefore, the label bakla can closet them into the performance of an identity that does not necessarily resonate with what they feel inside.

Labels have power in shaping a person. The rural and poor baklas grow up with an idea of who they are, and this idea can direct the choices that they make and actions that they take. In the context of rights, self-concept and identities are important because they affect what people think are crucial for them to live a life of dignity.

All are equal and are entitled to a life without discrimination and to be protected by the law. Paying attention to which kinds of protection that people need, then, significantly depends on the challenges brought about by the identity that they and the society recognize.

The lesson here for fellow gender rights advocates is simple: asserting and exercising human rights are not linear nor one-directional. They require retrospection and introspection. They necessitate the scrutiny of the very concepts that we use to define ourselves and other people. They need us to free ourselves from the limits of templates. Asserting human rights require us to recognize that the use of labels are loose instead of fixed, and because these labels are malleable, they can be shaped and reshaped, owned and denounced, constructed, and deconstructed by the very people they define.

In the fight for equality, moving forward is looking backward, and in terms of the rights of the LGBTQIA+, we can advance only if we are able to look back and understand how different labels and templates have manifested differently across individuals. When we therefore fight for the rights of the LGBTQIA+, we must also consider that one of the rallying experiences and one of the rallying identities that we employ may actually be limiting to some.

Finally, it is important to see the constraining dimension of the process of liberation. The more we understand this, the more we are able to push for human rights and assert them in the face of a government that sits on the violations of these rights. – Rappler.com

Athena Charanne 'Ash' R. Presto graduated summa cum laude and teaches at the Sociology Department of the University of the Philippines-Diliman. She is currently taking her MA in Sociology at the same institution. She tweets at @sosyolohija.