MANILA, Philippines – Every year, around 20 tropical cyclones visit the country, on top of rains from the southwest monsoon or hanging habagat, as well as thunderstorms that are all too common during the rainy season.

The National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council (NDRRMC) hopes that through its emergency mobile alerts, citizens can be informed of what to expect and what they must do.

The NDRRMC and telecommunications companies are required by law to send free mobile alerts before disasters happen. This is mandated under Republic Act No. 10639 or the Free Mobile Disaster Alerts Act.

"These alerts, if you already know your area, you know the characteristics of where you live, this EAWM (emergency alert and warning message) is just a reminder to the people of what you're supposed to do," NDRRMC 24/7 Operations Center Officer-in-Charge (OIC) Aimee Menguilla said in an interview with Rappler.

How it works: As soon as the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA) issues an advisory, the NDRRMC drafts a message to send to telcos, who in turn will send this to its customers.

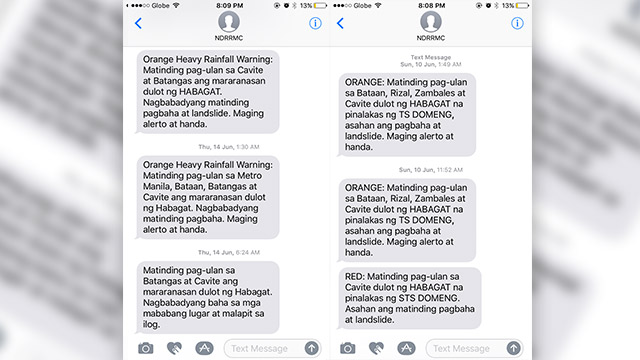

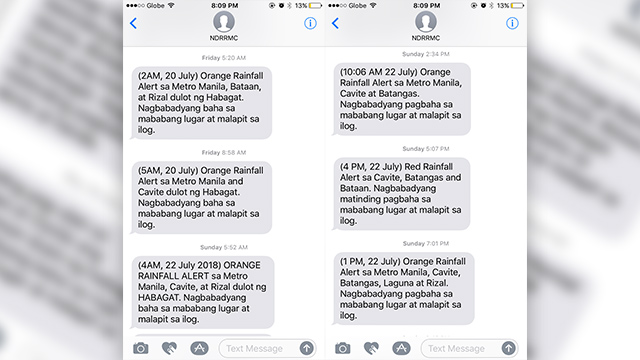

For rainfall warnings, the NDRRMC sends mobile alerts for PAGASA's orange and red warnings. (READ: How to use PAGASA's color-coded rainfall advisory)

Menguilla said the emergency messages would inform citizens of what to expect in their area over the next 3 hours, as rainfall is expected to continue over this period.

For instance, PAGASA's orange rainfall warning means intense rainfall has been observed for an hour and is expected to continue for the next two hours. Menguilla said this gives the message a time frame of about 3 hours.

Menguilla also said emergency warnings may be based on advisories of the Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (Phivolcs) on earthquakes and volcanic activity.

The process of drafting an alert message and then sending it to telcos can take up to about 10 minutes.

"We translate it into those short messages so the description of the message is hazard-specific, area-focused, and time-bound," Menguilla said.

The problem: Citizens have reported receiving delayed warnings. For instance, a mobile alert received at 9:17 pm was for a PAGASA rainfall warning issued at 4 pm. That's a delay of more than 5 hours, and by that time, a new warning would have been issued already.

The NDRRMC said the issue of timing is largely due to limitations of mobile devices and messaging systems.

According to NDRRMC Information and Communications Technology OIC Kelvin Ofrecio, two types of message broadcast systems are used to send alerts: short messaging system (SMS) and cell broadcast service (CBS).

CBS can send messages to cellphones based on subscribers' location, to pre-arranged cell sites. It also enables location-specific alerts without the need to register cellphones.

Of the two systems, CBS is quicker to send alerts, though not all mobile phones are equipped with this feature.

"We are implementing both types of systems. Siyempre, bawat system, merong limitation 'yung technology (Of course, both systems have limitations in their technology)," Ofrecio said.

"'Yung CBS, ito 'yung ginagamit sa ibang bansa. Ito 'yung tinatawag na instantaneous na 'pag dinala ng telco, within 3 to 5 seconds, matatanggap na ito ng recipient. However, hindi natin siya ma-fully implement dahil hindi lahat ng handset ay compliant sa cell broadcast feature," he added.

(CBS is used in other countries. It's instantaneous because recipients can receive alerts within 3 to 5 seconds after telcos send them. However, we cannot fully implement this as not all handsets are compliant with the cell broadcast feature.)

Given this limitation, the NDRRMC and telcos resort to SMS to send alerts, which takes much more time as messages are sent "point-to-point" unlike CBS' "point-to-multiple-point" system.

"Ang nangyayari, ang NDRRMC nagpapadala sa Bulacan [ng] red rainfall warning, at doon sa area na [pinapadalhan] niya, kunwari mayroong two million subscribers, magkakaroon ng two million seconds [of] queuing time kasi point-to-point ito," Ofrecio explained.

(What happens is, if the NDRRMC sends a red rainfall warning alert to Bulacan, and in that area, there are two million subscribers for example, there will be two million seconds of queuing time because it is point-to-point.)

If you're one of those who received warnings hours after they were issued, Ofrecio said chances are those warnings were sent via SMS rather than through CBS.

Moving forward: Unfortunately, there are no quick fixes to delayed warnings at the moment, since not all phones are CBS-compliant.

It could also be the case that CBS is turned off by default in mobile phone settings.

Telcos earlier clarified that some older phones, even those made more than 15 years ago, are capable of receiving cell broadcast messages. But this feature could be turned off by default.

Ofrecio also urged the public to check if emergency alerts are enabled in their mobile phone settings.

For Android users, one can go to messaging settings and look for Emergency Alerts or Cell Broadcast.

For iOS users, update to the latest version of the operating system, go to Settings, then Notifications, and scroll down to turn on Emergency Alerts. – Rappler.com