MANILA, Philippines – Progressive and forward-thinking, the country's capital is emblazoned with rainbow colors and crowded with all genders chanting for equality every Metro Manila Pride March.

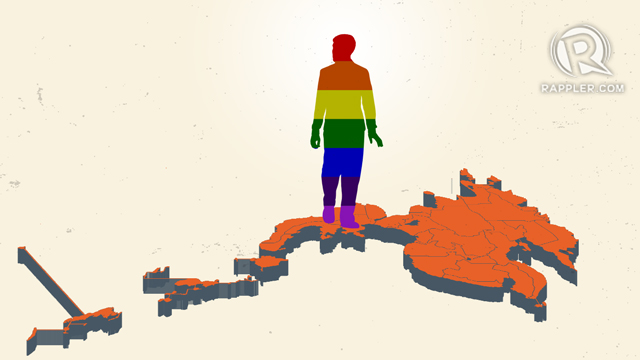

Like the Pride March, most LGBT-friendly movements are still centralized in Metro Manila. Other regions continue to lag behind in addressing the concerns of the sector, especially those in less developed spaces and areas of conflict.

Even until now, LGBT Muslims, especially those from Mindanao, are part of an underrecognized sector of the community. (READ: Is the Philippines really gay-friendly?)

Homosexuality as 'haram'

Rhadem Camlian Morados, an openly gay filmmaker from Zamboanga City, has struggled to reconcile his sexual orientation with his Muslim roots. Much of Muslim society regards homosexual acts as haram or forbidden by Islamic law. In turn, Muslim parents often disown their gay children. Though the Qur’an states homosexuality is sinful and should be corrected, it does not specify the punishment. (READ: On being gay and Muslim)

Part of Rhadem’s trial with his sexuality stems from his family roots. He faced even more pressure as his father is a high-ranking police officer and his grandfather is a Muslim priest or imam. Additionally, one of his grandfather’s brothers is the governor of Basilan, while another is one of the founders of the Moro National Liberation Front. There were strong expectations to be masculine and to uphold the family name.

“I grew up in an environment where there’s a really strong conservative-like masculinity where you need to be strong – there’s no room for softness, and you cannot taint the family name,” Rhadem explains.

As Rhadem is open with his identity, many have doubted his commitment to his religion

“A lot of people always question my faith. They were like, ‘Oh you’re gay, so you’re not Muslim,’” he shares.

Though most Muslims claim they accept gay people, this often comes with certain conditions. Morados discusses how Muslim society tends to be more open with the idea of homosexuality when this doesn’t involve the family.

“Some Muslims naman, they’re like, ah, we tolerate, we accept gay people, but not within our family. You know, there’s a sort of bias there where it’s convenient for them,” he says.

He observes that most Muslims “fear what they do not know,” until it is properly presented to them. During his missions for the Teach Peace Build Peace Movement, he reached out to different communities in conflict areas and connected with many conservative Muslim Mindanaoans in spite of his sexual orientation.

“I think it’s really a nice message. Like, now there’s this one family in Marawi...these are conservative Maranao, that after what we did, our psychosocial therapy, aid activity and whatsoever, and helping the refugees, they have seen the human side, the flaws of the LGBT," he adds.

Policy and protection

Arnold Jarn Ford Buhisan from Misamis Oriental is a training specialist for the Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program of the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD). Arnold identifies as gay. With his line of work, he combines his day job with his advocacy for LGBT rights through gender and development training.

Since the creation of DSWD’s Gender and Development division, Buhisan has been working on SOGIE training modules that address multiple concerns of the LGBT community. DSWD employees nationwide are mandated to undergo gender sensitivity trainings.

“Ang goal naman talaga ng Gender and Development ay pagcreate ng gender-responsive systems and processes ng government. At hindi lang government, outside the government also. So when you say gender-responsive, lahat ng mga processes, ay always in consideration with the LGBT sector,” he explains.

(The goal of Gender and Development is to create gender-responsive systems and processes in government. And not just within the government but also outside the government. So when you say gender-responsive, all processes are always in consideration with the LGBT sector.)

Mindanao still lacks in common LGBT initiatives and facilities typically centralized in Metro Manila, such as support groups, and gender-neutral restrooms. Buhisan stresses the importance of having these facilities readily available to the LGBT community in Mindanao.

“Government policies, responsive sa needs ng mga LGBT, 'yun yung pinakawala sa Mindanao, na nakikita ko na importante talaga. Kasi, if you have issues na LGBT issues at concerns, saan ka pupunta sa Mindanao?” he says.

(Mindanao lacks the most in implementing government policies that are responsive to the needs of the LGBT, which I think are really important. If you have issues that involve LGBT concerns, where will you go in Mindanao?)

The case of Mindanao

Islam is the second largest religion in the Philippines, and 94% of the country’s Muslim population is in Mindanao.

Considering the conservative nature of the religion, paired with the lack of gender-responsive government systems, the LGBT community in Mindanao faces unique struggles in grappling with their identities, sexualities, and reputations. (READ: [OPINION] The extra struggles of the LGBTQ+ community in Mindanao])

Both Rhadem and Arnold have received remarks about not conforming to prevalent gay stereotypes. Some of these stereotypes reduce gay men to hairdressers and makeup artists, as well as flamboyant crossdressers.

“Hindi ibig sabihin na being an LGBT ay kailangan magsuot in a certain way, nagsestereotype na dapat suot ka pambabae. The question is always na, 'Bakit hindi ka nagsusuot ng mga pambabae? 'Di ba LGBT ka?' Parang 'yun lagi ang tanong sa probinsiya,” Buhisan explains.

(Just because you’re a member of the LGBT community, that doesn’t mean you have to dress a certain way, and you’re stereotyped to dress like women. The question is always, “Why aren’t you wearing clothes for women? Aren’t you LGBT?” It seems like that’s always the question they ask in the province.)

Trumping with pride

Rhadem and Arnold are both core members of Mindanao Pride, an LGBT movement and organization for Mindanaoans. They hope that the pride march in Cagayan de Oro city will encourage LGBT Mindanaoans to come forward with their personal and collective trials.

“Nakakatuwa kasi noong nagstart ang Mindanao Pride, parang nakita ko na ang path towards advocacy sa Mindanao. Kasi, finally, may entry point ang Mindanao,” Arnold says.

(It’s heartwarming because when Mindanao Pride started, I finally saw the path towards advocacy in Mindanao. Because, finally, Mindanao has an entry point.)

Mindanao Pride aims to gather several LGBT organizations to march together and to celebrate diversity amid prevalent prejudices in their communities.

Rhadem envisions the event will serve as a political statement, as LGBT Mindanaoans will become more visible to local government officials as well as their needs and concerns. In light of the Bangsamoro Basic Law to be finalized in July, Rhadem hopes local government will finally be able to address the needs of the LGBT sector.

“At least we were able to establish strong LGBT groups and community all over Mindanao, so that once they implement, whether federalism or Bangsamoro, they can no longer say that you cannot be gay. Because in politics, number is power,” he explains.

Additionally, Rhadem hopes Mindanao Pride will provide a “state-sponsored safe space” for gay Mindanaoans who are afraid to come out, and to provide them with the proper support.

“I think it’s also a political campaign to show our local politicians and lawmakers that if you wanted to stay in power, you need to respect gay people,” he says. “I envision that in the near future, you cannot campaign for public office without knocking on the LGBT doors. ‘Cause we exist, and we can no longer hide in the shadows.” – Rappler.com

Gaby N. Baizas is a Community intern at Rappler, and an incoming senior at the Ateneo de Manila University. She is an AB Communication major under the journalism track.